Yesterday, I attended a small Linguistics colloquium lead by Gaja Jarosz concerning Sonority Sequencing in the Polish language. After listening somewhat intently, taking some notes and completing some Google searches, I had more or less figured out what these words meant and so I’ll attempt to explain the results of this research. Jackson, I apologize in advance for my attempt at explaining linguistics ☺

In psychology, linguistics, philosophy and really all inquiries concerning human understanding, there has been an ongoing discussion over whether the capacity for certain human abilities, like language development, intelligence, perception etc…, is hereditary and thus passed down through the human genome, or if these abilities are acquired as a result of exposure to one’s environment—more generally considered as the “Nature vs. Nurture” debate. Jarosz’s research focuses particularly on the universality of sonority in language development.

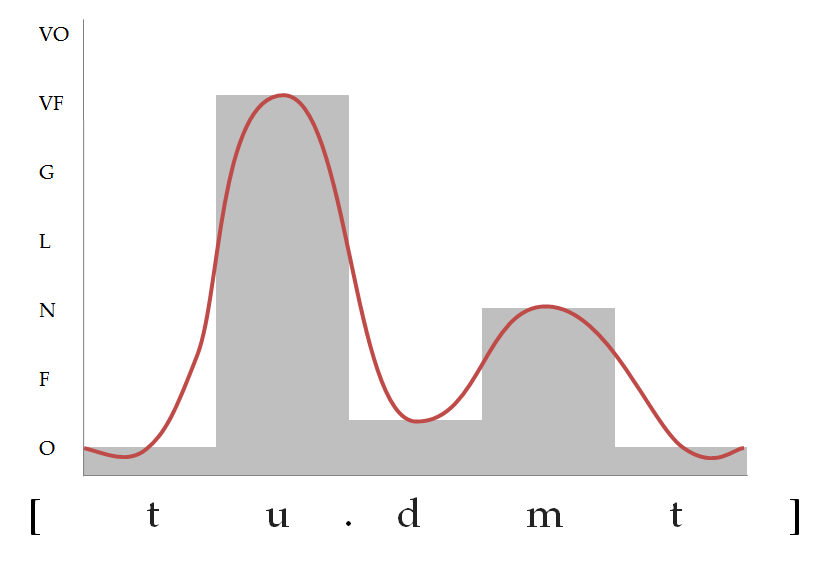

Sonority is the ranking of individual speech sounds, or “phones” in terms of their amplitude. So, if someone were to pronounce the vowel [u], the volume of this utterance would be louder than if the phone [t] were pronounced. As a result of this difference in volume, the structure of individual syllables within word segments represents a hierarchy. In English, the sonority scale looks like this:

[a] > [e o] > [i u] > [r] > [l] > [m n ŋ] > [z v ð] > [s f θ] > [b d ɡ] > [p t k]

Note: these are not letters from the English alphabet, but rather representations from the International Phonetic Alphabet or IPA.

In a word like “trust”, the sonority scale begins at [t], which is the quietest/least sonorous phone. Next comes [r]. Then [u], which represents the peak of sonority with the highest amplitude, and so on descending to [s] and [t] at its completion. In such monosyllabic words, vowels tend to be preceded and/or followed by consonants systematically. This idea, known as the Sonority Sequencing Principle (SSP), is both detected and violated across a variety of different languages, and thus provides some juiciness for researchers attempting to learn more about the origins of language development.

The Sonority Sequencing Principle would basically govern fundamental components of language without any other stimuli from the environment. However, prior research shows that computational models can detect the statistical preferences for distinct phones in children’s speech, which would only be acquired through exposure to language and require no reference to instinct. So it would make sense to say that children organize the syllabic structure of words as a result of continued phonological exposure to their language, rather than maintaining something innate for guidance, like a sonority hierarchy. Jarosz attempts to test the principle’s universality first by moving away from English, which is tested frequently for SSP, since the language does not adequately distinguish between popular hypotheses of nature vs. nurture. Instead, Jarosz uses Polish because the statistical models that detect SSP in a language like English cannot do so in Polish, since Polish has words like “Przepraszam”, which commonly strings 2-3 consonants together. (This wasn’t her exact example but hopefully it makes sense)

Interestingly, her results indicated that Polish-speaking children are still sensitive to SSP despite the language’s violation of the principle. By the logic, the results would suggest that SSP lies somewhere apart from the raw stimulus-to-pattern developmental processes of language since speakers who should not respond to SSP are still aware of its process. Jarosz concluded that Polish did not act as evidence for language development deprived of stimulus (as the Nature argument would suggest) but rather that the Polish language seems to defy the stimulus. So no answers…only more questions.

It should be noted that Jarosz only tested 4 Polish children twice, which is not really convincing as far as experimental processes go. Nonetheless, these findings do provide a means for further research, and thus the bellows for the fiery Nature vs. Nurture debate will keep on pumping.